Last week was a bit of a first for us and myself. We (the River Restoration Centre) held our first full day online hydromorphological training course with a virtual field work component!

Due to the Covid-19 outbreak, we have been unable to offer our usual series of training courses in person. The challenge here was to develop a course that provide the same kind of experience as the one we normally run that includes a very important field component where participants can directly experience hydromorphological processes and forms as well as pressures and impacts of modifications.

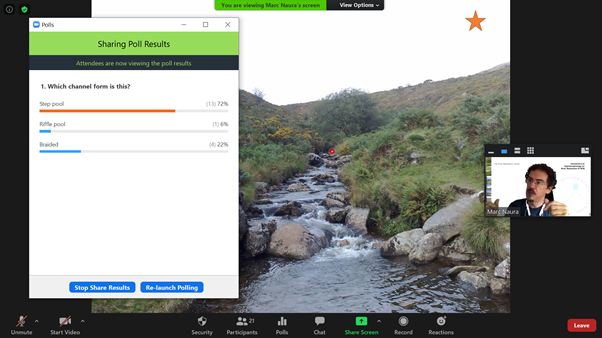

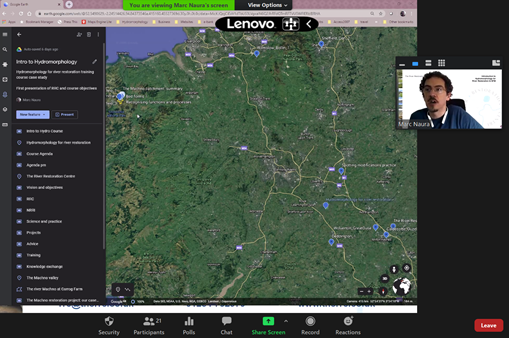

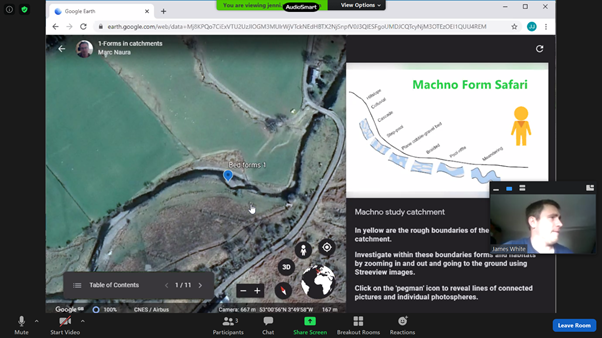

So we have been busy designing new ways of offering the same experience online by adding virtual site visits and even fieldwork. We delivered the Introduction to Hydromorphology (Level 1) training course using a combination of Zoom and Google Earth software. Fifteen delegates joined us on the Zoom call with regular switches to Google Earth and Streetview to demonstrate and experience hydromorphological processes forms and drivers virtually using one of our case study catchment on which we collected a lot of 360 photographs. Polls were set up to ask the delegates questions, and create as much of an interactive session as possible to keep everybody’s attention alive.

The crux of the course was to introduce delegates to a framework for analysing catchment and river processes, forms and how they are influenced by modifications and land management. This was achieved through formal short presentation followed by group work, in pairs, in the air and on virtual ground using Google Earth online, 360⁰ photos, and historic maps.

Delegates worked in pairs through tasks to spot features and modifications, think about processes, and map pressures. Finally, delegates were asked to assess everything we had gone over in the training and offer justified restoration options. This was a great opportunity to go over all the concepts we had been introduced to, and brainstorm ideas.

Feedback from the course has been really encouraging, and we are now looking at adapting the rest of our courses online and run more this Summer and Autumn. We are also considering adapting the River Habitat Survey course, potentially turning the existing presentations that are delivered in a training room into a series of online modules with virtual field work, and organising site visits separately over a few days to practice doing the survey whilst maintaining social distancing rules. We will be in touch with more information soon and we would welcome your suggestions.

In the meantime, please visit the RRC website to view our training events and please email us rrc@therrc.co.uk if you are interested in attending a virtual training course.